Don't ask me why I bothered — well, OK, blame a pile of ironing — but does anyone else think this film plays like a batty parody of early Tennessee Williams? I do declare...

Don't ask me why I bothered — well, OK, blame a pile of ironing — but does anyone else think this film plays like a batty parody of early Tennessee Williams? I do declare...

Thursday, November 30, 2006

Crimes of the Heart

Don't ask me why I bothered — well, OK, blame a pile of ironing — but does anyone else think this film plays like a batty parody of early Tennessee Williams? I do declare...

Don't ask me why I bothered — well, OK, blame a pile of ironing — but does anyone else think this film plays like a batty parody of early Tennessee Williams? I do declare...

Monday, November 27, 2006

Supporting Actress Smackdown: 1974

A shout-out once again to StinkyLulu, the web hostess with the mostest and our monthly go-to-gal for debating the issues that really matter. In this case it's who deserved Best Supporting Actress in 1974, when by unanimous consensus Ingrid Bergman pulled a Zellweger and defeated four better rival performances than her own (in the stuffy and smug Murder on the Orient Express). By no one's reckoning was it a great year for the category — co-smackdowner Nick thinks it might even have been the worst ever — but I differ in having enjoyed the comic va-va-voom Madeline Kahn injects into the otherwise rancid Blazing Saddles, the blowzy vitality of Diane Ladd as a harassed diner waitress in Scorsese's Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore, and the touching, flavourful work of Valentina Cortese (the overall favourite) as a diva crumbling on set in Truffaut's faintly disappointing film-about-filming Day for Night. Plus, I was the only one who had much time for Talia Shire in The Godfather, Part II, debate about whom still rages in the comments below. Do you hate her or rate her? Post away. Mention has been made of the unnominated, as ever: Karen Black, who I dimly remember being marooned and miscast like almost everyone in The Great Gatsby, Kahn and the hysterical Cloris Leachman in Young Frankenstein, and, my personal picks, the even more memorable double-act of stay-at-home girlfriends Ann Prentiss and Gwen Welles in Altman's fantastic California Split. (Pic above, and a tip: Altmaniacs wanting to commemorate his passing in some way could do a lot worse than tracking down this underappreciated flick. I think it's one of his very best.) Next month: 1975, and another one.

A shout-out once again to StinkyLulu, the web hostess with the mostest and our monthly go-to-gal for debating the issues that really matter. In this case it's who deserved Best Supporting Actress in 1974, when by unanimous consensus Ingrid Bergman pulled a Zellweger and defeated four better rival performances than her own (in the stuffy and smug Murder on the Orient Express). By no one's reckoning was it a great year for the category — co-smackdowner Nick thinks it might even have been the worst ever — but I differ in having enjoyed the comic va-va-voom Madeline Kahn injects into the otherwise rancid Blazing Saddles, the blowzy vitality of Diane Ladd as a harassed diner waitress in Scorsese's Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore, and the touching, flavourful work of Valentina Cortese (the overall favourite) as a diva crumbling on set in Truffaut's faintly disappointing film-about-filming Day for Night. Plus, I was the only one who had much time for Talia Shire in The Godfather, Part II, debate about whom still rages in the comments below. Do you hate her or rate her? Post away. Mention has been made of the unnominated, as ever: Karen Black, who I dimly remember being marooned and miscast like almost everyone in The Great Gatsby, Kahn and the hysterical Cloris Leachman in Young Frankenstein, and, my personal picks, the even more memorable double-act of stay-at-home girlfriends Ann Prentiss and Gwen Welles in Altman's fantastic California Split. (Pic above, and a tip: Altmaniacs wanting to commemorate his passing in some way could do a lot worse than tracking down this underappreciated flick. I think it's one of his very best.) Next month: 1975, and another one.

Review: Stranger Than Fiction

Or: A Little Bit of Literary Theory is a Dangerous Thing. I’ve seen worse films in 2006, but few have made me physically squirm so often with the shallow and stretched quality of their core conceit: that glum IRS accountant Harold Crick (Will Ferrell), insofar as he’s a human being at all, exists in the imagination of a highly annoying, chain-smoking and we suspect not very talented author of death-obsessed novels about The Way We Live Now (Emma Thompson, frankly all over the place). Stranger Than Fiction is perilously pleased with itself and has almost nothing to say, but I was at least hoping for a little charm and deftness of tone, some effective comedy, from such an obviously featherweight effort. In the event, Zach Helm’s debut screenplay, which I have a nasty feeling will pick up this year’s easily-pleased Match Point Oscar nomination, is the precise opposite of good Charlie Kaufman (heavy concepts, light touch) in that it handles its wafty, overfamiliar ideas with great clumsy gauntlets by way of pretending they add up to something. Ferrell is fine as a flummoxed nobody, but as Harold runs around trying to decide if his life conforms to comedy or tragedy, we’re yanked from the film’s nominal comparison-points Adaptation or The Truman Show (as if!) to altogether less inspiring memories of Melinda and Melinda. As for Marc Forster, he’s hired the same d.p. and production designer who made his barely-seen Stay (2005) a gruellingly pretentious watch: they’re evidently much bigger fans of art, books, modernist architecture and psychoanalysis than they are of, say, tax officials, which means that while Harold’s apartment and office are of the low-ceilinged, airless variety of your typical drone worker, everyone else’s look almost dangerously hip and urban. (I bet their next film’s some kind of trippy psychological thriller about a boutique hotelier.) Naturally I wanted to like Maggie Gyllenhaal, who played a gold-digging rebel to utter perfection in Don Roos’ Happy Endings, but even her performance as a seditious baker (!) goes instantly wrong here — how does Forster bungle so much, with a cast of this calibre? After this and Stay I’m almost ready to mount a rearguard defence of the admittedly twee Finding Neverland as its director’s least precocious, fussed-over project, but every one of us has more of a life than Harold and, fingers crossed, better things to do with it. C—

Monday, November 20, 2006

Review: Hollywoodland

The wacky miscasting of Adrien Brody as a dissolute gumshoe, which almost every review I’d read, good and bad, had suggested was this film’s biggest mistake, turns out to be not only the least of its problems but, to me, its sole point of peripheral interest. I’m certainly not going along with the “It’s a bird! It’s a plane! No, it’s Ben Affleck acting!” wave of praise, since the latter’s job — playing 1950s TV Superman George Reeves, found dead at the film’s start, as a tragic washout — is just the easiest excuse ever for an obviously limited star to cash in on his shortcomings. Nor did I have much time for an ineffectually brittle Diane Lane as his mistress, the wife of a sinister studio chief (Bob Hoskins), because director Allen Coulter has even less, virtually complicit with faithless George in his decision to underlight her big woman-spurned monologue, quite brutally, and thus deny her an affecting sign-off of any kind. The movie achieves no pathos for Affleck or Lane’s characters even when it thinks it does, and its aim — to dredge up and make us really feel the linked tragedies of a couple of has-been celebrities — is undone by your discovery, within minutes, that it’s a has-been in itself, lifeless and grey on the slab.

No, the only spark of curiosity for me was watching Brody collude in the flimsy pretence that he’s in some way “investigating” Reeves’s death, when the interspersed flashbacks bear little or no relation to any clues he’s actually finding, conversations he’s having, or anything much in the framing sequences at all. What’s the point of his case? I couldn’t find one, until — wait for it, fans of tenuous metatextual games for critics with nothing better to do — the suggestion that Reeves had his role in From Here to Eternity snipped to shreds put me in mind of Brody’s similar fate on The Thin Red Line, another James Jones adaptation. I’m not done: Brody’s dismissive treatment of sheepish cop Dash Mihok, who beat him with a larger if still minor role in Malick’s film, encouraged me yet further in my utter boredom to read Hollywoodland as in fact its misplaced leading man’s smirking idea of comeuppance, now that he’s got his Oscar. The film is devoid, after all, of plausible notions elsewhere about how movie stars are meant to manage their careers, and try as I might I could find no other workable point of connection between Brody’s Louis Simo and the pitiful Affleck-as-Reeves. If Brody keeps signalling his superiority to the material, as I’ve read in plenty of other reviews, it’s because he is superior to it, and heaven knows I’d rather be watching him flirt gamely with his own miscasting than anyone — Daniel Craig? — trying on a Ralph Meeker impression in a manner you could call apropos for such a silly part. I can’t recommend Hollywoodland in the slightest, really, but I have a feeling I’ll always look back on this particular inglorious moment as Brody’s graduation to fully-fledged stardom. Stardom and all the lunacy and industrial compromise that term entails — not because he's very suitable for this non-role in an insultingly drab period mystery, but because he’s so unmissably wrong and steals it anyway. D

Thursday, November 09, 2006

Doubly deflowered

I had a free afternoon today, so went to catch a bargain screening of Brian De Palma's The Black Dahlia at the West End's only real second-run venue these days, the wonderfully (and, for this movie, aptly) disreputable Prince Charles Cinema. With its voluminous red curtains, upwardly sloping floor and old-fashioned instruction that patrons might want to contemplate shutting the hell up for the next two hours, the Prince Charles fosters a sense of hushed, dirty occasion even at 3.15pm on a cold and darkening Thursday, and it's one that this much puzzled-over movie met deliciously. I like the fact that I like The Black Dahlia, quite a lot — I like the fact that I'm not supposed to. No one could argue that De Palma's film was more satisfying, shapely or in any conventional way better than Curtis Hanson's LA Confidential, but I think I could have a good stab at positing it as a truer, more faithful distillation of James Ellroy's prose, in that's it's sleazy, not classy, jagged not smooth, and that, not to put too fine a point on it, large chunks of the thing simply don't add up. In all the ways that Hanson and Brian Helgeland's screenplay for the earlier film "improves" on Ellroy, I think they're also doing him a vague disservice, and it's one which De Palma, like the scuzzball voyeur he is, intuitively rectifies.

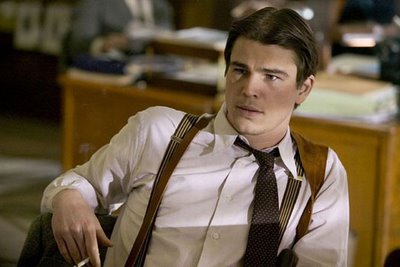

The truth is, though there have been several (not many) better American movies this year, there have been very few which not only warrant but actively demand a second viewing like this does, and many of the things that might have failed to work for you first time round simply don't matter on a return visit. I still don't get the whole business with Blanchard's ill-gotten gains at the end, for instance, perhaps because De Palma's direction (or my attention) were at their least focused on both viewings when major plot points were being wrapped up, but who cares? Of the lead quartet, only Scarlett Johansson strikes me as completely wrong for her part, I still have a whole load of time for the faintly affected stylings of Hilary Swank, whose peculiar look and accent could only belong in this movie, and Josh Hartnett's weary, sexy, inwardly and outwardly scarred embodiment of Bucky Bleichert is not only easily his best work to date but my pick for the most underrated male performance of the year. It's telling how much of Mark Isham's propulsive score is cued directly into tiny movements of Hartnett's face — he can blink, without a word, and send the film barreling down whole new avenues of intrigue on a hunch. I need hardly add that Fiona Shaw and Mia Kirshner continue to amaze in small parts of such rich, distinct colouration that it felt like going back in to watch them carry on those performances rather than repeat them. All told, whatever, it's still a mess of a movie in some crucial ways, but I think it's a good mess. A fine mess. I stand by my original grade and then some. B

PS. Do comment. Who else has seen a movie twice this year and what changed?

Wednesday, November 08, 2006

Monday, November 06, 2006

Review: This is England

Shane Meadows could be British cinema’s best-kept secret — a poet of pratting about, lippy banter, and boys doing what they’re best at, which is being hopeless. For a good 45 minutes, This is England — Meadows’s first attempt at a period piece, and certainly his most ambitious movie to date — seems such safe ground for this talented dosser that we’re lulled into a false sense of security: the movie’s joshing ensemble and bang-on Thatcher-era detail are confidently interwoven, the young actor Thomas Turgoose is a tremendously natural and cheeky find as the 11-year-old adopted as a mascot by a gang of skinheads, and the Falklands war is sensibly submerged by way of backdrop to the point where more tellies are tuned into the vintage ITV quiz show Blockbusters than the tank-and-plane-filled news broadcasts. (Sadly, adorable host Bob Holness is only heard, not seen.)

If we have some inkling that the film’s going to tip over into something darker, it could be that we’ve seen Meadows’s marvellous A Room for Romeo Brass (1999), still his best feature to date, and one which the debuting Paddy Considine practically broke in half with an unanticipated and terrifyingly casual outburst of mid-movie sociopathy. This is England wants to make a similar shift, and also to use a single intervening personality to get us there, which is to say from laddish comedy to race-baiting melodrama. That person is Combo (Stephen Graham), recently paroled and a skinhead with issues, unlike the gregarious and welcoming Woody (Joseph Gilgun), the chubby, put-upon Gadget (Andrew Ellis), his ironically-named West Indian comrade Milky (Andrew Shim) and the rest of the gang.

From Combo’s arrival onwards, Meadows’s previously sure direction starts to falter in small but damaging ways, and the more the picture strains for controversy and impact, the less it ends up having. Two big transitional scenes misfire, back to back — first an accidentally soothing blanket of string score, welling up on top of one of Combo’s screeds, fails to highlight the tensions within the group and instead all but papers over them, uniting the rest of the gang and ourselves in a sort of head-shaking compact of awkward awareness. This mistake carries over into the next, crucial Combo scene and contrives to disable his rhetoric so fundamentally we can’t believe anyone, let alone Turgoose’s previously hard-to-kid Shaun, is actually talked round.

The moment the appalled Woody and pals leave the scene, there’s a dismaying sense that Meadows has transferred all his eggs to the wrong basket, and the absence of the decent and appealing Gilgun from pretty much the whole of the rest of the movie is painfully felt. We get big sequence after big sequence from here on, starting with a nationalists’ convention addressed by Meadows regular Frank Harper in the manner of a village butcher in his Sunday best, and then numerous confrontations between Combo and his cohorts, but big sequences aren’t really Meadows’s forte, and the shortage of interstitial bits of comic business or even many Turgoose close-ups during the film’s second half compounds its schematic crudity. The scenario works if and only if Shaun is convincingly persuaded to be a racist, but not from Graham’s Combo are we going to get the chillingly charismatic advocacy of, say, Edward Norton in American History X: he’s just a thug, emotionally stunted and patently troubled, and the performance isn’t multi-layered enough to disguise or underplay these traits until their explosive revelation, in a powerfully acted scene with Milky, later.

However we slice it, the force of Combo’s personality is less than enough to get Shaun on side, so there’s also the memory of the boy’s dad, a Falklands casualty, to get him thinking, and it’s here that Meadows wishes to make an uneasy equation between violence at home and the sputtering legacy of British military imperialism overseas. Thomas Clay’s critically panned The Great Ecstasy of Robert Carmichael, intercutting its savage rape with images of Churchill and the Gulf War, took this same line of thinking to a notably senseless extreme, but while there’s nothing comparably pretentious in Meadows’s picture, what he’s actually trying to say remains disappointingly woolly and ill-thought-through. As a state-of-patriotism bulletin, This is England just seems to be going through the motions, and Shaun’s apparent conversion away from a racist mindset, mainly through a bloody kicking administered to Milky, by Combo, in a fit of self-pitying jealousy right near the end, is just as sudden and dramatically convenient as his lapse into it. This in itself might work if we felt impressionable little Shaun (shorn!) was still under the sway of mercurial, daily-shifting playground allegiances, which the early part of the film auspiciously suggests he is, but not many 11-year-olds have to carry the symbolic burden of a St George’s flag around or make a life decision using it, and the fact that Shaun is required to as part of his steep late-in-the-picture learning curve is a clear indication that we have Bigger Fish To Fry. Despite all the problems I’ve outlined, the movie is well worth wrestling with, and I don’t for a second regret that Meadows has attempted to make it, but I think his canvas is too small for the points he wants to get across, those points actually obscure the character detail he really excels at, and if he’d given Shaun slightly fewer of his big fish to cart around, the little ones might have made a filling meal all by themselves. B—

Thursday, November 02, 2006

Cool Hollywood Couple no. 472

I love Annabella Sciorra, and I didn't know she was seeing Bobby Cannavale. That makes me wildly jealous of them both. I can't wait to see her in Twelve and Holding, and him in Cuban-Italian-American Studs' Wild and Wacky Jockstrap Party. Oh wait. That's not a film.

Let's leave the kid out of it, OK?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)